Epinephrine is a drug that we use frequently in the ICU as a vasopressor/inotrope. It’s my go to drug when a patient has hypotension that is related to poor contractility. It’s a great drug to start for cardiogenic shock. But, as Rishi Kumar points out here, it’s a super versatile drug.

Category: Shock/Resuscitation

IV Bicarb: Is There Any Value?

IV Bicarbonate used to be all the rage in critical care. It was included in the ACLS algorithms. It was used, in drips or in pushes, to treat all kinds of problems. I’ll admit, there are still times that I use it when the indication is…shaky, often when my back is against the wall and I need something to buy some time. But, is there any real use for it in ICU practice? In a recent episode of The Elective Rotation, Pharmacy Joe recently took a look at when IV bicarb should be avoided (often) and when it is helpful (a lot less often).

Often, IV bicarb is used as a band-aid. This is ok to a point. If it helps buy you some time, ok. But using it without addressing the underlying issues (like I remember doing a lot in the old days) is fraught with problems. There are a handful of scenarios where we should avoid using bicarb because it’s been shown to be of no value. ACLS has removed it from the algorithms and generally avoids against its use in cardiac arrest, for example. But there are some specific times when it is helpful and should be considered.

Fluid Boluses

We frequently give fluid boluses to patients in the ICU. And a not infrequent question I’ll get from the nurses is, “do you want that on the pump or on a pressure bag?” Does it matter? My usual response is, “whatever,” unless the patient is crashing in which case I opt for the pressure bag. Why? Because they need fluid faster than 999ml/h (which is as fast as the IV pump will go). 999ml/h sounds like a lot until you think about it. That would take an entire hour for a liter bolus to go in. In urgent resuscitation, that’s too long. You can see from this chart that the flow rate of even a 20g IV is a lot more than that.

But, Dr. Eddy Joe Gutierrez makes a pretty solid argument that even if it’s not an urgent situation where we all assume the fluid needs to get in fast, we should be using pressure bags. It has to do with the fact that not all of that fluid ends up in the vascular space. And over time, more and more of it with extravasate out. So, when a liter of crystalloid given over 1 hour, only 200ml will end up staying in the vessel. Hardly enough to raise the SV and thus the MAP. So, maybe we should always be using pressure bags for fluid boluses? His Instagram post below summarizes it nicely, but you should definitely give the entire post a read here.

The Rule of 15

I tweeted about this yesterday but wanted to do a whole post on it, because I think it’s a great tip! ABGs and acid-base disturbances are difficult topics to grasp. There are lots of great ways to remember how to interpret these, and we’ll cover them in time. But one of the hardest parts, especially for learners, seems to be the concept of proper compensation. How do I know if this primary problem is all that’s going on or if there is more? With anion gap metabolic acidoses, we teach students to use Winter’s Formula to calculate the expected pCO2 and thereby determine if you’re dealing with a purely metabolic problem, or if there is a concomitant respiratory derangement as well.

Of course, you can always use your handy ABG analyzer app (ABG Eval is my personal favorite), but what if you just want to know quickly? You can use the Rule of 15. Dr Jeremy Faust (@jeremyfaust on Twitter) mentioned this in a thread I was reading yesterday and it sparked my interest. I retweeted his tweet, but wanted to know more. I found a very quick video that he does along with Dr Corey Slovis on Academic Life in Emergency Medicine (ALiEM, another great resource for critical care education!). Basically, take the bicarb and add 15. That should give you roughly the expected pCO2 and if you throw a “7.” in front of it, roughly the expected pH. Watch the video here for more!

POCUS in Shock: the RUSH Exam

POCUS can be an extremely helpful tool in approaching the patient with undifferentiated shock. The RUSH exam (or more properly, the RUSH protocol, it’s actually a set of POCUS exams packed together for efficiency and ease of memory) was developed for use in the ED, but it is equally useful in the ICU. In the original protocol, the exams are done in a specific order based on the likelihood of the cause. However, in the ICU I often adapt it based on what I already know about my patient (in a patient who just had a big belly surgery I might start with the abdomen, for example). Additionally, this exam is a good starting point for novice sonographers as it incorporates lots of different exams and doesn’t require the use of advanced techniques (like M-mode, color, or measurements). Scott Weingart over at EM:CRIT does a nice overview here, including some recent updates from Jacob Avilla from 5-Minute Sono and some good resources.

Here is a card I made for my students to help use the findings from RUSH to differentiate shock states.

Push Dose Pressors

You’re intubating a patient who is hemodynamically tenuous, or worse, was hemodynamically stable prior to induction. After administration of the sedative they become hypotensive. In many cases, the hypotension doesn’t present immediately because of the sympathetic stimulation of the laryngoscope. But once the tube is in and things settle down, the BP starts to drop. What do you do? This is almost always a transient problem. Do you need to start a drip? Anesthesiologists and an increasing number of EM providers use something called “push dose pressors.” Little boluses of vasopressor agents that can bolster your patient’s blood pressure to get them through a transient drop. In this article on Critical Care Now, Ruben Santiago covers the Pearls and Pitfalls with Push Dose Pressors. Although he approaches this from a ED perspective, the concepts are the same for transient hypotension associated with sedation in the ICU.

Propofol and Hypotension

Propofol is a super common medication that we use for induction prior to intubation and for maintenance of sedation in the ICU. One of the big downsides of its use is the risk of hypotension. In this episode of the Elective Rotation podcast, Pharmacy Joe addresses the question “Can hypotension from propofol be predicted?” Although we can and do often use push-dose pressors to deal with this temporary hypotension from propofol and other similar agents in RSI scenarios, there are other situations where adequate sedation with propofol can lead to hypotension. In these situations, are the only answers to switch sedatives, tolerate inadequate sedation, or start vasopressor infusions? Nope. Give this episode a listen to discover more about predicting who will become hypotensive and how to prevent it (in some cases). Listen here.

Are Diuretics Safe in Critically Ill Patients?

One of the more important (and overlooked) aspects of critical care is the concept of de-resuscitation. We give lots of fluid to patients in the throws of shock of all kinds, but even though that fluid resuscitation may be life saving at the time, it can lead to lots of complications later on. So, we need to de-resuscitate these patients and often the best way to do that is with diuresis. But, are diuretics safe to give in the critically ill? In this episode of the Elective Rotation podcast, Pharmacy Joe discusses the safety and efficacy of diuresis in the ICU. Listen here.

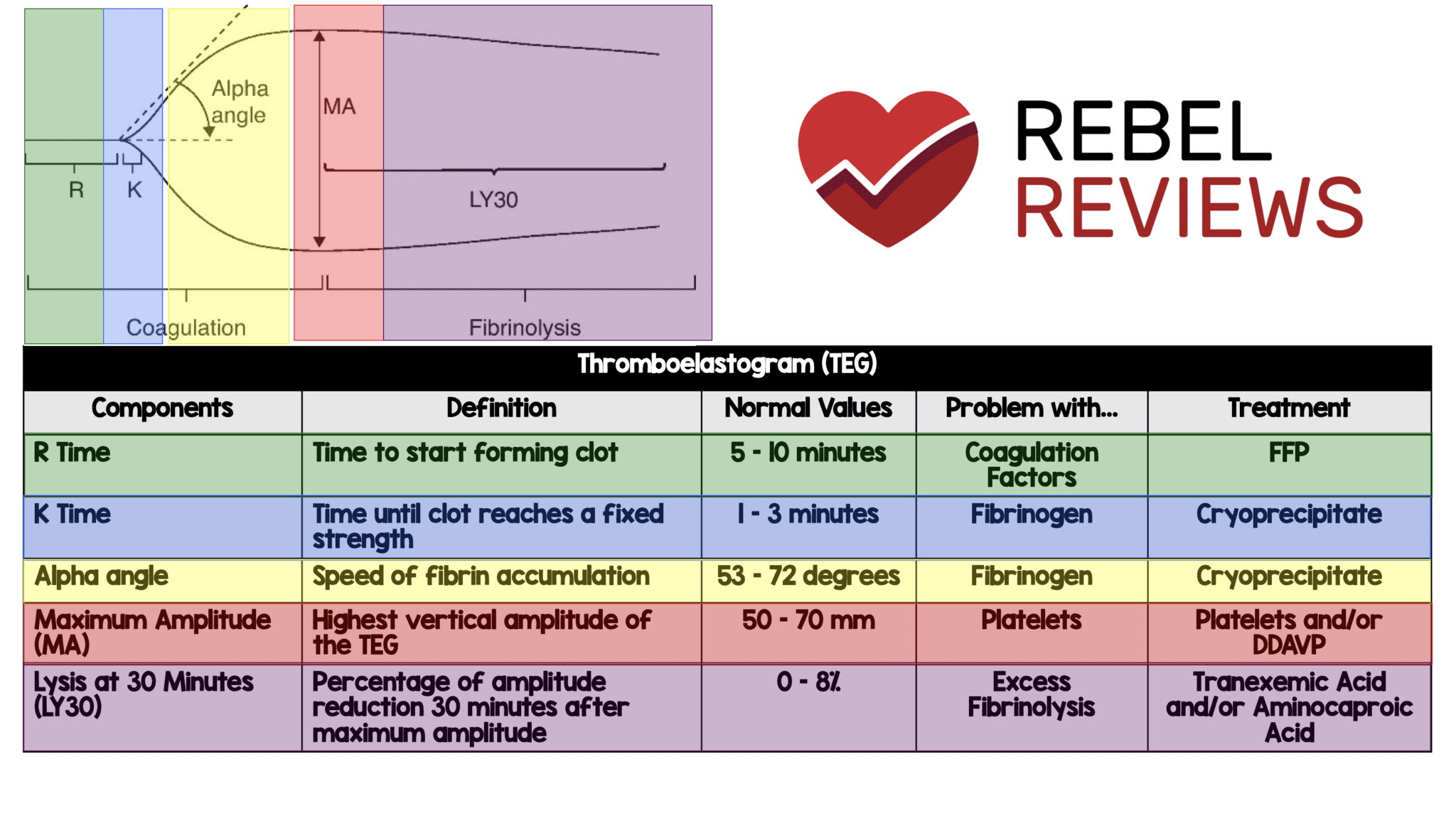

Thromboelastogram (TEG)

If you’re a visual learner like me, you’ll appreciate this TEG quick reference from REBEL EM. It not only covers what you need to know about reading a TEG, but what to do about the abnormal results.